Robert Mitchum é Harry Powell, um pregador psicótico que se casa com a viúva Willa Harper (Shelley Winters) depois de saber pelo defunto marido, o seu antigo companheiro de cela, Ben Harper (papel interpretado por Peter Graves, o Jim de Mission: Impossible), que esta tem consigo uma pequena fortuna resultante do assalto a um banco. Quem afinal tem o dinheiro guardado é John, o filho de Willa, e Powell, depois de assassinar friamente Willa (numa cena cuja fotografia nos remete para o expressionismo alemão de O Gabinete do Dr. Caligari) inicia uma perseguição a John e sua irmã que culminará no confronto com Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish), a figura matriarcal que irá fazer frente ao perverso pregador.

Robert Mitchum é Harry Powell, um pregador psicótico que se casa com a viúva Willa Harper (Shelley Winters) depois de saber pelo defunto marido, o seu antigo companheiro de cela, Ben Harper (papel interpretado por Peter Graves, o Jim de Mission: Impossible), que esta tem consigo uma pequena fortuna resultante do assalto a um banco. Quem afinal tem o dinheiro guardado é John, o filho de Willa, e Powell, depois de assassinar friamente Willa (numa cena cuja fotografia nos remete para o expressionismo alemão de O Gabinete do Dr. Caligari) inicia uma perseguição a John e sua irmã que culminará no confronto com Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish), a figura matriarcal que irá fazer frente ao perverso pregador.Tal como a descrição acima citada de Laughton indica, o filme não pretende ter um cariz realista, e sente-se, de facto o ambiente de sonho, aliás, pesadelo, que percorre os 93 minutos de fotografia a preto e branco. Mitchum incarna na perfeição - numa das melhores interpretações da sua carreira - a figura ambígua, inquietante e ameaçadora da personagem, ensaiando neste controverso papel aquela que viria a ser a sua famosa imagem de marca, o semblante duro e sério que tantas vezes apreciámos nos westerns e films noir (e não só) que protagonizou.

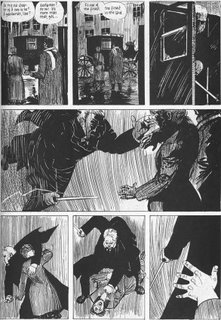

Robert Mitchum is Harry Powell, a psychotic preacher who marries widow Willa Harper (Shelley Winters) after her late husband, his former cellmate Ben Harper (played by Peter Graves, Mission: Impossible’s Jim), has told him that she keeps a small fortune from a bank robbery. As a matter of fact, the one who keeps the money is John, Willa’s son, and Powell, after coldly murdering Willa (in a scene with a photography that reminds us of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’s German expressionism) starts a pursuit of John and his sister which will end with the confrontation with Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish), the matriarchal figure who will face the perverted preacher.

In the simplistic regard of this film as a tale/religious allegory, one can see Harry Powell as the incarnation of evil in constant fight with good (this fight is attested in his sermons) and John Harper as the bearer of the heavy burden of sin – the money from the robbery – who walks his redeeming path towards the discharge of that load which, after all, prevents him from reuniting with his lost childhood.

Just like Laughton’s quotation above indicates, this film doesn’t mean to have a realistic quality, and one actually feels the dreamlike, or nightmare-like, ambience, through the 93 minutes of black and white photography. Mitchum perfectly incarnates – in one of the best performances in his career – the ambiguous, disturbing, threatening figure of the character, rehearsing in this controversial role what would be his famous trademark, the hard and stern (in)expression that so many times we’ve enjoyed in the westerns and films noir (and other genres) where he starred.

The film contains many theatrical elements and is covered with a vision of opposites that emphasize an underlying Manichaeism: strong contrasts of light and shadows, religious images that portray resistance and innocence but also the evil inherent to man and, finally, the words love and hate that Powell has tattooed on the fingers of his right and left hand, respectively. The reactions to Laughton’s unique (literally!) work, to this nightmare-tale that leaves no-one indifferent, are usually extreme, as well. I’m pleased with that, for that is a frequent quality in an exceptional work.