20 April 2007

31 January 2007

O gótico de Goethe * Goethe's gothic

O mito de Fausto, germânico na sua origem e confundindo-se com o Fausto histórico, passou por inúmeras variações, quer a nível de género literário – tragédia, lírica, romance – quer a nível temático. Doktor Faustus de Thomas Mann – a história do compositor Adrian Leverkühn – é a obra emblemática deste afastamento estrutural, em que a base do mito é mantida, sofrendo no entanto uma descontextualização para penetrar no universo musical.

O mito de Fausto, germânico na sua origem e confundindo-se com o Fausto histórico, passou por inúmeras variações, quer a nível de género literário – tragédia, lírica, romance – quer a nível temático. Doktor Faustus de Thomas Mann – a história do compositor Adrian Leverkühn – é a obra emblemática deste afastamento estrutural, em que a base do mito é mantida, sofrendo no entanto uma descontextualização para penetrar no universo musical.Mas de todos os Faustos conhecidos na história da literatura europeia, o Faust de Johann Wolfgang von Goethe é o que frequentemente se considera como a tragédia de Fausto por excelência, pela sua complexidade e riqueza dramáticas, e por introduzir o tema da sedução, inédito até à altura e que, segundo Camille Paglia, lhe foi emprestado por Don Juan e Casanova.

Goethe personificou a viragem pela qual o doutor Fausto deixa de ser o exemplo do herege medieval que sofre as consequências de ter escolhido o caminho do Mal, para se tornar no símbolo iluminista do século dezoito e na incarnação do homem da civilização ocidental. Fausto é, em Goethe, o homem que se redime por ter sido motivado pela sua paixão para com a verdade através da razão e do conhecimento, conceitos fundamentais do século das luzes.

A tragédia está dividida em dois espaços simbólicos logo definidos no início de Prolog im Himmel pelos arcanjos (vv. 243-270). O Sol e a Luz do divino são os símbolos supremos de um cosmos ordenado e de mistérios impenetráveis, enquanto que a terra é apresentada como o palco de um violento jogo de forças entre a Luz e as Trevas.

O percurso de Fausto pode ser equiparado a uma viagem em que o viajante é orientado por um guia. De início, este guia – Mefistófeles – assume o comando e o percurso é escolhido por ele, devido à ignorância do viajante nestes caminhos inéditos. À medida que a viagem se desenrola, é o próprio Fausto quem vai aprendendo a dispensar a ajuda de Mefistófeles, tornando-se progressivamente independente dele para efectuar a escolha de caminhos mais nobres.

Nessa viagem, o itinerário principal é a procura do complemento feminino de Fausto, e embora não seja essa a intenção inicialmente demonstrada, é para esse destino que Mefistófeles o vai transportar. Desde a descoberta de formas imperfeitas de erotismo em Auerbachs Keller e a emergência do desejo sexual em Hexenküche, até à revelação do Eterno Feminino após a sua morte, Fausto experimentará duas paixões amorosas que correspondem a dois momentos da viagem em que o seu nível de independência intelectual é bastante distinto. A relação com Margarida corresponde ao período de infância intelectual e sexual, enquanto que no acto de Helena estamos perante um Fausto já em plena maturidade e consciente dos resultados que podem advir dos seus actos.

Fausto, tal como Dorian Gray, não hesita em entregar a sua alma. De algum modo, a busca de Fausto dirige-se para a imortalidade, não no sentido estrito, mas como uma procura de eternização de cada momento da vida, através do labirinto que constantemente a simboliza; imortalidade significa aqui também uma entrada no reino do espiritual, símbolo do poder criativo que Fausto poderá adquirir.

Fausto, de Johann W. Goethe, está publicado em português pela Editora Relógio d’Água, com a centenária tradução de Agostinho d'Ornellas e prefácio de Paulo Quintela, e mais recentemente (1999) com a belíssima tradução de João Barrento.

21 December 2006

Portugal segundo Vieira * Portugal according to Vieira

18 November 2006

O elogio da loucura * In praise of folly

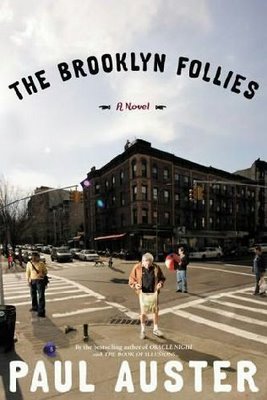

Quem narra a história é Nathan Glass, um angariador de seguros reformado que resolve tornar-se um autodidacta das letras, e é preciso ser-se um grande autor como Auster para assumir este risco de deixar um fraco escritor como Nathan controlar a narrativa e ainda assim deslumbrar o leitor. Talvez porque há coisas que só conseguem assumir uma grande expressividade através das palavras simples de uma pessoa simples – a honesta e até ingénua capacidade de encantamento e de ilusão torna-se mais credível na voz do ignorante que do homem sábio. Ou num outro ângulo, e usando uma analogia shakespeariana, Iago não profere plenamente as palavras de acusação, ele sabe que o efeito será mais devastador se for o próprio Othello a verbalizar o corolário da suspeita que o irá destruir.

Apesar de tudo, o Auster de sempre está lá: mais uma vez um começo abrupto – I was loking for a quiet place to die; outra vez uma personagem-escritor; outra vez um livro-dentro-do-livro; outra vez Brooklyn; outra vez uma vontade incomensurável mas insatisfeita de que certos pormenores, que nos são acenados en passant, tivessem sido mais desenvolvidos porque temos a certeza que neles se escondem outros filões – não seria a primeira vez que Auster transportava um detalhe, uma personagem ou uma situação de um romance para o desenvolver noutro; outra vez tantos traços que constituem, com propriedade, o que já se pode intitular de estilo austeriano - mas não austero... Repetitivo? Nem pensar. Apesar de tantos referenciais e traços comuns, The Brooklyn Follies é uma obra completamente nova, e não o é apenas pelo estilo imposto pela voz do narrador que, aos olhos do leitor de Auster é como a Coca-Cola do slogan pessoano, primeiro estranha-se, depois entranha-se.

The Book of Human Folly, o livro dentro de The Brooklyn Follies, o aglomerado de pequenas histórias, episódios, frases soltas e descrições que Nathan Glass vai escrevendo e revelando ao longo do romance é uma verdadeira caixa de surpresas e mostra bem o talento de Auster para compor anedotas da vida humana com uma grande dose de verosimilhança (já comprovado também no seu National Story Project que resultou na colectânea True Tales of American Life). São elas as anedotas que compõem os traços da anedota maior, pois anedótica é também a vida de Nathan, que, como bom comediante da vida, encontra um parceiro à altura da comédia, o volumoso sobrinho Tom Wood, desaparecido da sua vida há anos e reencontrado em Brooklyn nesta nova fase da(s) sua(s) vida(s). As associações podem ser inúmeras, desde a parelha cómica de Laurel e Hardy à estática união tragicómica de Vladimir e Estragon, mas certo é que a relação das duas personagens acaba por converter-se, em grande medida, no motor que impulsiona a acção.

Poderia ainda, em conclusão, referir as temáticas abordadas ao longo das “follies”, elas próprias as “follies” da vida – a paixão, a amizade, a velhice, o sonho, a homossexualidade, a ambição, o desencantamento… – mas todos esses aspectos, e muitos outros, significam apenas uma nova roupagem para o grande fio condutor, a intemporalidade que começamos a encontrar padronizada na obra de Auster: o caminho percorrido pela vida humana, repleto de acasos, coincidências, desvios, regressos, surpresas, encontros e desencontros e, acima de tudo, muitas loucuras.

12 September 2006

A casa dos horrores * The house of horrors

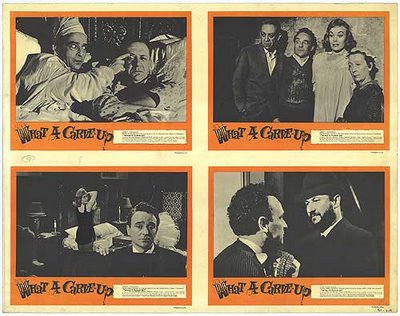

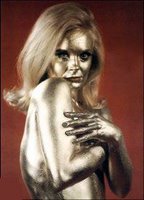

A actriz britânica Shirley Eaton (1937-...) ficou imortalizada na

história do cinema pela sua participação em Goldfinger (1964) de Guy Hamilton, o terceiro da série James Bond protagonizado por Sean Connery: apesar de relegada para segundo plano pela ‘bondgirl’ Honor Pussy Galore Blackman, ninguém esquecerá o corpo de Eaton completamente coberto de tinta dourada. Alguns anos antes desse banho de spray dourado, Shirley Eaton protagonizou What a Carve Up! (1961), uma comédia negra de Pat Jackson (baseda livremente em The Ghoul (1933) de T. Hayes Hunter), que, se bem que a comparação seja, a meu ver, um pouco depreciativa e até injusta, se aproximava um pouco do estilo da fastidiosa série de filmes de comédia Carry On.../Com jeito vai... (30 filmes entre 1958 e 1978, mais uma tentativa de 'reanimação' em 1992 - é obra!).

história do cinema pela sua participação em Goldfinger (1964) de Guy Hamilton, o terceiro da série James Bond protagonizado por Sean Connery: apesar de relegada para segundo plano pela ‘bondgirl’ Honor Pussy Galore Blackman, ninguém esquecerá o corpo de Eaton completamente coberto de tinta dourada. Alguns anos antes desse banho de spray dourado, Shirley Eaton protagonizou What a Carve Up! (1961), uma comédia negra de Pat Jackson (baseda livremente em The Ghoul (1933) de T. Hayes Hunter), que, se bem que a comparação seja, a meu ver, um pouco depreciativa e até injusta, se aproximava um pouco do estilo da fastidiosa série de filmes de comédia Carry On.../Com jeito vai... (30 filmes entre 1958 e 1978, mais uma tentativa de 'reanimação' em 1992 - é obra!).Este filme, e especialmente a cena em que Linda, a personagem representada por Eaton, é surpreendida a despir-se no quarto por um embaraçado Ernie (Kenneth Connor), constitui - juntamente com Yuri Gagarin, Orfeu (o de Jean Cocteau), tabletes de chocolate e cassetes de vídeo - uma das obsessões recorrentes de Michael Owen, o protagonista do romance de 1994

de Jonathan Coe que pediu emprestado o título ao filme de Jackson.

de Jonathan Coe que pediu emprestado o título ao filme de Jackson.A narrativa segue duas linhas paralelas, estabelecidas logo no prólogo e apresentadas ao longo da primeira parte sempre em capítulos alternados. Por um lado, o desvendar da vida do obscuro e angustiado escritor Michael Owen, que tem como fio condutor a misteriosa comissão da biografia de uma das mais ricas e influentes famílias britânicas - a família Winshaw. Por outro, a revelação dos membros da terceira geração dessa família - a narrativa enquadra precisamente três gerações de Winshaws (17 ao todo), o que tornaria as primeiras páginas do livro algo confusas, não fora o recurso a uma árvore genealógica logo no início do prólogo, cuja consulta ajuda o leitor a localizar as personagens na estrutura familiar. A informação narrada nestes capítulos é obtida a partir das pesquisas de Michael para a composição da biografia, incluindo fragmentos de programas de televisão, artigos de revistas, etc., o que nos faz seguir durante toda esta primeira parte a perspectiva de Michael, que por sua vez assume a dificuldade em manter a realidade separada da ficção à medida que se vai envolvendo cada vez mais com os Winshaws.

A segunda parte decorre na lúgubre mansão da família, onde é lido o testamento de Mortimer Winshaw. Nesta momento em que todas as peças do puzzle se encaixam através das esperadas revelações (como num jogo de Cluedo), num misto de romance de Agatha Christie e filme de Terence Fischer, vemos a oportunidade de Michael finalmente se encontrar cara a cara com os Winshaws que ainda estão vivos, apenas para confirmar através dos acontecimentos que a sua relação com a família ultrapassa o carácter profissional da escrita biográfica. Mais ainda, essa é a noite em que o escritor que desde criança vive obcecado com What a Carve Up! (o filme) confirma finalmente a sensação - que sente desde que o vira com nove anos - de que não é um mero espectador mas uma personagem que o vive por dentro sem qualquer controlo dos acontecimentos – facto corroborado pelo facto de Michael deixar de ser narrador na primeira pessoa e com o clímax no momento em que encarna Kenneth Connor e surpreende a sua própria Shirley Eaton no quarto da mansão, culminando assim o processo que se adivinha com o constante dejà vu da cena ao longo da narrativa.

A família Winshaw é um retrato cru e mordaz, centrado entre os mandatos conservadores de Margaret Thatcher e John Major, de uma Inglaterra literalmente despedaçada (carved up) por um pequeno grupo dominante que sistematicamente mina as reformas do Seviço Nacional de Saúde, arrasa sem escrúpulos o mercado bolsista, favorece artistas em troca de favores sexuais, inunda o mercado alimentar com carnes provenientes de criações com duvidosos métodos de rentabilização e vende armas a Saddam Hussein enquanto se espera que este invada o Kuwait (o livro foca com alguma persistência a ansiedade da expectativa de uma guerra do golfo que está iminente). Muito mais que uma simples sátira socio-política, esta narrativa é uma experiência de leitura extremamente completa e grandemente enriquecida através da mistura de géneros, e influências, especialmente as de origem cinematográfica: o cinema contamina claramente este livro, o que apesar de tudo não é surpreendente - não esqueçamos que Coe também se move nos meios cinematográficos tendo escrito biografias de Humphrey Bogart e de James Stewart.

This film, and especially the scene where Linda, the character played by Eaton, is surprised undressing in her room by an embarrassed Ernie (Kenneth Connor), is one of Michael Owen’s recurring obsessions – together with Yuri Gagarin, Orpheus (Jean Cocteau’s), chocolate bars and videotapes. Owen is the main character of the 1994 Jonathan Coe’s novel which borrowed the title from Jackson’s film.

The narrative follows two parallel lines, established right away in the prologue and presented throughout part one, always in alternate chapters. On the one hand, the disclosure of the live of obscure and anguished writer Michael Owen, which gravitates around the mysterious commission for the biography of one of the richest and most influent (and vilest) British families – the Winshaw family. On the other, the revelation of the members of the family’s third generation – the narrative encloses precisely three generations of Winshaws (17 of them), which would make the first pages of the book somehow confusing without the help of the family tree printed at the beginning of the prologue. It does help the reader locate the characters within the family structure. The information narrated in these chapters is obtained from Michael’s researches for the composition of the biography, including fragments of television programmes, magazine articles, etc., which makes us follow Michael’s perspective for the whole part one. He actually assumes how difficult it is to keep reality and fiction apart as he gets more and more involved with the Winshaws.

Part two takes place in the lugubrious family mansion, where Mortimer Winshaw’s will is read. At this moment in which every piece of the puzzle fits via the expected revelations (as in a Cluedo game), in a mixture of Agatha Christie’s novel and Terence Fischer’s film, we see Michael’s opportunity, at last, to meet the remaining Winshaws face to face, only to confirm through the events that his relation with the family goes far beyond the professional status of biographical writing. Moreover, that is the night where the writer, who had been obsessed with What a Carve Up! (the film) since his childhood, finally confirms the feeling – which he’d had since he first saw it at the age of nine – that he is not a mere spectator, but a character living it from the inside without any control of the events – fact confirmed by the fact that Michael stops being the first person narrator, and by the climactic moment where he embodies Kenneth Connor and surprises his very own Shirley Eaton in the mansion room, concluding thus the process one could guess with the constant dejà vu of this scene throughout the narrative.

The Winshaw family is a raw and poignant portrait, centred between the conservative administrations of Margaret Thatcher and John Major, of an England literally carved up by a small dominant group that systematically undermines the National Health Service reforms, ruthlessly knocks down the stock market, favours artists in return for sexual favours, fills up the food market with meat that comes from farms with dubious methods of cost-effectiveness and sells guns to Saddam Hussein while waiting for him to invade Kuwait (the book focuses persistently on the anticipating anxiety of an imminent gulf war). Much more than a simple socio-political satire, this narrative is an extremely comprehensive reading experience and one greatly enriched by the mixture of genres and influences, especially those of cinematic origin: cinema clearly crawls into the book, which, after all, is not surprising at all if we bear in mind that Coe also moves in the cinematographic media, since he wrote Humphrey Bogart and James Stewart’s biographies.

07 September 2006

Please insert coins

Game Over is an amusing stop-motion film for all those who miss the time when the attractiveness of videogames did not depend on a high-resolution, million-colour display with surround sound in the comfort of your couch, but on having, or not, enough coins in your pocket to remain a few more minutes in the arcade room trying to survive one more level. The honoured classics in this short film are Centipede, Frogger, Asteroid, Space Invaders and Pac-Man.

17 August 2006

21 July 2006

Velásquez e as vacas no país da Coca-Cola * Velasquez meets cows in the land of Coca-Cola

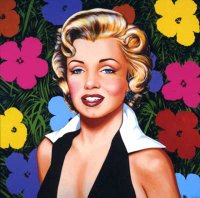

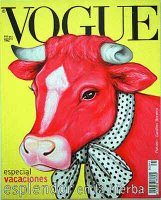

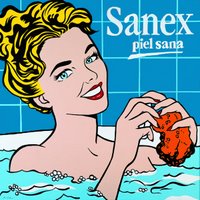

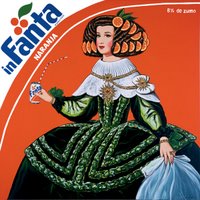

Anúncios ou artes plásticas? Quadros ou posters? Conceptualismo ou consumismo? Estas são algumas dúvidas pertinentes (ou não) que assolam quem espreita o universo da Pop Art em geral e, em particular, a arte do valenciano Antonio de Felipe (n. 1965). Como focos preferenciais - até à data - do seu trabalho de pintura, ilustração, escultura e instalação, Felipe elegou os temas da publicidade (com especial destaque para os logótipos comerciais), o cinema de Hollywood (particularmente retratos de ícones como Audrey Hepburn ou Marilyn Monroe), o pintor Diego Velásquez (uma série inteira homenageando o pintor do Barroco das Cortes Espanholas do século XVII, as suas Meninas e Infantas), retratos de celebridades tão diversas como a Madre Teresa e Claudia Schiffer e, finalmente,... as vacas (antes do advento da CowParade, vacas de todos os tipos e decoradas com inúmeros temas, recorrendo sobretudo à publicidade).

Anúncios ou artes plásticas? Quadros ou posters? Conceptualismo ou consumismo? Estas são algumas dúvidas pertinentes (ou não) que assolam quem espreita o universo da Pop Art em geral e, em particular, a arte do valenciano Antonio de Felipe (n. 1965). Como focos preferenciais - até à data - do seu trabalho de pintura, ilustração, escultura e instalação, Felipe elegou os temas da publicidade (com especial destaque para os logótipos comerciais), o cinema de Hollywood (particularmente retratos de ícones como Audrey Hepburn ou Marilyn Monroe), o pintor Diego Velásquez (uma série inteira homenageando o pintor do Barroco das Cortes Espanholas do século XVII, as suas Meninas e Infantas), retratos de celebridades tão diversas como a Madre Teresa e Claudia Schiffer e, finalmente,... as vacas (antes do advento da CowParade, vacas de todos os tipos e decoradas com inúmeros temas, recorrendo sobretudo à publicidade). A publicidade é, aliás, o motivo omnipresente na obra de Felipe, a que não é alheio o facto de ter trabalhado como director criativo numa agência de publicidade valenciana. O autor explica:

A publicidade é, aliás, o motivo omnipresente na obra de Felipe, a que não é alheio o facto de ter trabalhado como director criativo numa agência de publicidade valenciana. O autor explica:Estoy muy familiarizado con ese lenguaje y, por eso, he querido incorporarlo a mi obra.

obras, Felipe explica que isso não distorce o intuito original destas e afirma, não sem um boa dose de ironia:

obras, Felipe explica que isso não distorce o intuito original destas e afirma, não sem um boa dose de ironia:Estoy encantado de que, por primera vez, una marca que aparece en mis cuadros haya pagado por difundir mi obra. Es bueno para ellos y es bueno para mí.

Antonio de Felipe é um caso único no panorama da Pop Art espanhola. Antes dele e dignos de referência, só mesmo a Equipo Crónica, também formada em Valencia nos anos 60, (originalmente constituída por Manuel Valdés, Rafael Solbes e Juan António Toledo) e de cuja tradição do “poster pop” o próprio Felipe admite sofrer influência. Se a isso adicionarmos a

influência das figuras de Velásquez, as cores fortes de Warhol e Lichtenstein e a proveniência de uma região plena de luz, cor e fiesta – veja-se as Fallas de Valencia – entendemos de forma mais clara o universo figurativo e cromático do autor.

influência das figuras de Velásquez, as cores fortes de Warhol e Lichtenstein e a proveniência de uma região plena de luz, cor e fiesta – veja-se as Fallas de Valencia – entendemos de forma mais clara o universo figurativo e cromático do autor.Se, por acaso, passar por Marbella até ao fim deste mês, está patente na Galeria de Arte Pedro Peña uma exposição com 12 obras de Antonio de Felipe. Um complemento colorido e refrescante para apreciar ao vivo quando sair do calor da praia…

Advertising or Fine Arts? Paintings or posters? Conceptualism or consumerism? These are some pertinent (or not) doubts that occur to those who peek at the Pop Art universe in general and the art of the Valencian Antonio de Felipe (n. 1965) in particular. As a preferential focus – until now – of his painting, illustration, sculpture and installation, Felipe elected the subjects of advertising (with a special stress on commercial logotypes), Hollywood cinema (particularly portraits of icons such as Audrey Hepburn or Marilyn Monroe), the artist Diego Velasquez (a whole series as a tribute to the Baroque painter of the 17th century Spanish Courts, his Meninas and Infantas), portraits of celebrities as different as Mother Teresa and Claudia Schiffer and, finally,... the cows (before the advent of CowParade, all kinds of cows decorated with countless themes, especially resorting to advertising).

One of the idiosyncratic features of Felipe’s work is the crossover of distinct universes and their peaceful togetherness in a particularly humorous tone which, at the same time, explores a specific unifying concept (like Van Gogh’s Shoes with the Camper logo or Snow White biting Macintosh’s apple) and clearly discloses the influences that dwell in his work. The whole logotipos series resorts to this coupling between two fields of visual representation that would have nothing in common for a start – works of masters like Picasso, Van Gogh or Velasquez, or icons from the visual universe of animation or comic books (Disney, Hergé) interconnect with commercial brands such as Fanta, Pepsi, Kleenex or Dodot nappies, almost as if they had been conceived for that matter.

Actually, advertising is the omnipresent motif in Felipe’s work, and the fact that he worked as a creative director at a Valencian-based advertising agency is no coincidence. The author explains:

I am very familiar with that language and, therefore, I wanted to integrate it in my work.

If, on the one hand, the amusing reduction of these art objects to advertising images acts as a meditation on their iconographic value, on the other, the limit for the contamination that publicity exerts within the work of art is clearly challenged by the author, integrating in the paintings the logos of his sponsoring companies. Moving further towards this intrusion of advertising with the insertion of the very sponsors in the works, Felipe explains that it does not distort their original purpose and states, ironically:

I am delighted that, for the first time, a brand that appears in my paintings has paid to spread my work. It is good for them and it is good for me.

Antonio de Felipe is a unique case in the scene of Spanish Pop Art. Before him and worth of notice, there was only the Equipo Crónica, also formed in Valencia in the 1960s, (originally composed by Manuel Valdés, Rafael Solbes and Juan António Toledo) and whose “pop poster” tradition Felipe himself admits to have influenced him. If we add to that the influence of the figures of Velasquez, the strong colours of Warhol and Lichtenstein and a home region full of light, colour and fiesta – see Valencia’s Fallas – we understand more clearly the figurative and chromatic universe of the author.

If, by any chance, you happen to pass in Marbella by the end of this month, an exhibition with 12 works by Antonio de Felipe is being held at the Galeria de Arte Pedro Peña. A colourful and refreshing complement to enjoy alive after you leave the warmth of the beach…

11 July 2006

As vampiras lésbicas só atacam uma vez * Lesbian vampires only strike once

Quando observamos a história recente da música popular, deparamo-nos muitas vezes com fenómenos meteóricos, os chamados one-hit wonders. Ou porque são cirurgicamente fabricados com esse objectivo ou, mais frequentemente, porque grandes multinacionais da música assim o desejam, obrigando distribidores e media a impingir esse produto ininterruptamente, são temas que isoladamente atacam de forma impiedosa as tabelas de vendas e inundam as ondas hertzianas até à náusea - pobre daquele que ouse sequer ligar o botão do rádio ou da televisão sem saber que estação está sintonizada - apenas para, umas semanas depois, se evaporarem tão rapidamente como surgiram. Nalguns casos, os autores aparecem e desaparecem tão depressa como a sua música, noutros vislumbra-se claramente um golpe de sorte do infeliz artista que após o big bang se arrasta moribundo, de forma clownesca, sem perceber que um raio não cai duas vezes no mesmo microfone.

Citando dois exemplos coincidentemente do ano de 1993, quem não se lembra (infelizmente, a memória só se perde para as coisas que realmente importam) de What’s Up? daquelas criaturas com uns chapéus gigantes e disformes a esconder cabelos com ar de quem não vê shampoo desde que Copérnico descobriu a teoria heliocêntrica, as 4-Non Blondes (perdão, os 4-Non Blondes, pois o colectivo inclui um senhor de apelido Rocha - chegará a portugalidade também aos confins do aberrante?); ou a Macarena, o êxito que elevou grandemente o estatuto da já nobre profissão de polícia sinaleiro, usando os gestos do controlo do trânsito para pôr a população deste planeta a tremer tão massivamente os seus tecidos adiposos que só me espanta os fabricantes de gelatina não terem usado a ideia para uma campanha publicitária. Se bem se lembram, a canção era interpretada por um duo de senhores com pinta de angariadores de seguros na reforma, daqueles que ao fim do dia se sentam na marisqueira a devorar gambas e imperiais, os decrépitos Los del Río. Poderia ainda referir dezenas de outros exemplos, como o Aserejé/The Ketchup Song das cordovesas Las Ketchup, mas vou-me abster de mais comentários, até porque as moças espanholas têm um ar simpático e já não têm mãos a medir com as acusações de - pasme-se - satanismo e invocação de forças malignas em Aserejé (a-ser-herege).

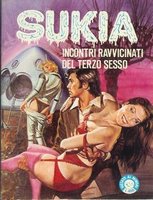

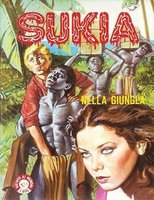

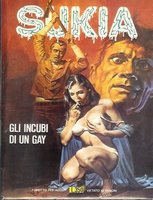

Tudo isto vem a (des)propósito dos Sukia, a banda que, não tendo sido uma one-hit wonder, tem um percurso que se aproxima muito da trajectória meteórica destas, motivo pelo qual me ocorreu a introdução deste texto. Os Sukia lançaram um primeiro álbum daquilo que prometia vir a ser uma interessantíssima carreira musical sob vários pontos de vista, mas acima de tudo com um experimentalismo singular que procurava fundir várias proveniências musicais e sonoras. Mas Contacto Espacial con el Tercer Sexo, afinal, não viria a ter sucessor e o quarteto formado por Sasha Fuentes, Ross Harris, Grace Marks, e Craig Borrell não mais voltaria a dar que falar deixando para além deste álbum, apenas mais dois singles retirados dele, Gary Super Macho (em CD e vinil 12'') e The Dream Machine (apenas em vinil 12'').

Os Sukia foram buscar o seu nome à vampira lésbica protagonista da série de banda-desenhada para adultos com o mesmo nome, e surgiram em Los Angeles, em 1996, no contexto da célebre cena musical de Silverlake, a mesma comunidade musical por onde se moviam Beck, os Beastie Boys ou os Dust Brothers (sendo estes últimos os produtores de Contacto Espacial...). Qualquer um dos quatro elementos principais do colectivo se aventura por distintos instrumentos, e esta facilidade multi-instrumental ajuda a configurar o ecléctico mosaico que forma a música dos Sukia. E quando se fala em instrumentos, é necessário encarar a palavra no seu sentido mais lato, pois as fontes sonoras estendem-se por uma vasta colecção de sons encontrados (como transmissões da NASA ou discos de hipnose) que é conjugada com vocalizações ora ritmadas, ora fantasmagóricas, assentes sobre uma colagem pairante de teclados (onde o moog domina), caixas de ritmos primitivas ou sopros que nos remetem para estéticas mais orquestrais, entre outras sonoridades.

O ambiente criado é, portanto, multi-facetado, e encontramos elementos que oscilam entre o glamour nostálgico da space age pop e da exotica, misturados com o som lo-fi dos equipamentos e samples retro, e características que remetem mais para um lounge de vanguarda futurista. Tudo isto contribui para uma recriação instrumental fascinante e cuja estranheza inicial se transforma rapidamente numa atracção ao mesmo hipnotizante e alienante, carregada também de um sentido de humor necessário à confirmação de um carácter mais lúdico e despretensioso.

Com um resultado tão atraente e uma crítica extremamente positiva na recepção do álbum, seria, pois, de esperar uma continuação do projecto, mas entretanto passaram dez anos e... nada, nem um sinal! Sukia, onde estão vocês?

Let me give you two examples, coincidently both from 1993: who doesn’t remember (unfortunately, memory is only lost for things that do matter) What’s Up? by those creatures with gigantic shapeless hats hiding hair that looked like they hadn’t seen a drop of shampoo since Copernicus discovered the heliocentric theory, the 4-Non Blondes; or the Macarena, the success that significantly brightened the meaning of the noble job of traffic policeman, by using traffic control gestures to put this planet’s population shaking their adipose tissue so massively that I’m amazed by the fact that jelly manufacturers haven’t used the idea for an advertising campaign. If you remember well, the song was interpreted by a duo of gentlemen who looked like retired insurance policy sellers, the kind that sit at the local pub in the evening stuffing themselves to oblivion with crisps and pints, the decrepit Los del Río. I could still mention dozens of other examples, such as Las Ketchup’s The Ketchup Song/Aserejé, but I’ll refrain from further comments, mostly because the Spanish girls actually look nice and already have a handful of problems with the accusations of – imagine – Satanism and summoning of malign forces in Aserejé (a-ser-herege = let’s be heretic).

All this talk is (not) related to Sukia, the band that hasn’t been a one-hit wonder, but has had a course very similar to this kind of meteoric trajectory, and ultimately that’s why the introduction above emerged. Sukia released the first album of what seemed to be the promise of a very interesting musical career under several points of view but, above all, with a unique experimentalism that sought to merge different music and sound sources. But Contacto Espacial con el Tercer Sexo, after all, didn’t have a sequel and the quartet formed by Sasha Fuentes, Ross Harris, Grace Marks, and Craig Borrell would no more be spoken about leaving, besides this album, only two other singles drawn from it, Gary Super Macho (in CD and 12'' vinyl) and The Dream Machine (only in 12'' vinyl).

Sukia borrowed their name from the lesbian vampire character in the adult comic book series with the same name, and they came out in Los Angeles, in 1996, amidst the famous Silverlake musical scene, the very same musical community where Beck, the Beastie Boys or the Dust Brothers dwelled (these latter were the producers of Contacto Espacial...). Any of the four main elements in the band feels comfortable with different instruments, and this multi-instrumental ease helps configure the eclectic pattern that makes up Sukia’s music. And when you talk about instruments, you have to use the word in its broadest sense, for Sukia’s sound sources stretch through a vast collection of found sounds (such as NASA transmissions or records on hypnosis) which are put together with vocals sometimes rhythmic, sometimes eerie, set on a floating collage of keyboards (where the moog dominates), primitive drum boxes or brasses that take you to more orchestral aesthetics, among other sounds.

The created ambience is thus varied and you can find elements that oscillate between the nostalgic glamour of space age pop and exotica, mixed with the lo-fi sound of retro equipment and samples, and qualities that take you to a lounge of futuristic avant-garde. All this contributes to a fascinating instrumental recreation that causes an initial awkwardness that is quickly transformed into an attraction at the same time mesmerising and alienating, also loaded with a sense of humour which is needed to confirm a more playful and unpretentious character.

With such an attractive result and extremely positive reviews in the reception of the album, one would therefore expect a sequel of the project, but in the meantime ten years have passed and... nothing, not even a sign! Sukia, where are you?

The only thing we have left is to enjoy the suggestive illustration of some of the comic book covers that inspired the band’s name... (see above)

03 July 2006

O homem na lua * Man on the moon

Quem está familiarizado com a obra de Paul Auster reconhecerá diversos temas recorrentes que lhe são transversais - demandas recheadas de eventos causados por e causadores de coincidências (ou sincronicidades, na perspectiva psicanalítica de Jung) ou as vidas errantes cujo caminho invariavelmente termina no abandono e na degradação voluntária da condição humana como factor essencial para um auto-conhecimento.

Quem está familiarizado com a obra de Paul Auster reconhecerá diversos temas recorrentes que lhe são transversais - demandas recheadas de eventos causados por e causadores de coincidências (ou sincronicidades, na perspectiva psicanalítica de Jung) ou as vidas errantes cujo caminho invariavelmente termina no abandono e na degradação voluntária da condição humana como factor essencial para um auto-conhecimento.28 June 2006

O pregador predador * The predator preacher

Robert Mitchum é Harry Powell, um pregador psicótico que se casa com a viúva Willa Harper (Shelley Winters) depois de saber pelo defunto marido, o seu antigo companheiro de cela, Ben Harper (papel interpretado por Peter Graves, o Jim de Mission: Impossible), que esta tem consigo uma pequena fortuna resultante do assalto a um banco. Quem afinal tem o dinheiro guardado é John, o filho de Willa, e Powell, depois de assassinar friamente Willa (numa cena cuja fotografia nos remete para o expressionismo alemão de O Gabinete do Dr. Caligari) inicia uma perseguição a John e sua irmã que culminará no confronto com Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish), a figura matriarcal que irá fazer frente ao perverso pregador.

Robert Mitchum é Harry Powell, um pregador psicótico que se casa com a viúva Willa Harper (Shelley Winters) depois de saber pelo defunto marido, o seu antigo companheiro de cela, Ben Harper (papel interpretado por Peter Graves, o Jim de Mission: Impossible), que esta tem consigo uma pequena fortuna resultante do assalto a um banco. Quem afinal tem o dinheiro guardado é John, o filho de Willa, e Powell, depois de assassinar friamente Willa (numa cena cuja fotografia nos remete para o expressionismo alemão de O Gabinete do Dr. Caligari) inicia uma perseguição a John e sua irmã que culminará no confronto com Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish), a figura matriarcal que irá fazer frente ao perverso pregador.Tal como a descrição acima citada de Laughton indica, o filme não pretende ter um cariz realista, e sente-se, de facto o ambiente de sonho, aliás, pesadelo, que percorre os 93 minutos de fotografia a preto e branco. Mitchum incarna na perfeição - numa das melhores interpretações da sua carreira - a figura ambígua, inquietante e ameaçadora da personagem, ensaiando neste controverso papel aquela que viria a ser a sua famosa imagem de marca, o semblante duro e sério que tantas vezes apreciámos nos westerns e films noir (e não só) que protagonizou.

Robert Mitchum is Harry Powell, a psychotic preacher who marries widow Willa Harper (Shelley Winters) after her late husband, his former cellmate Ben Harper (played by Peter Graves, Mission: Impossible’s Jim), has told him that she keeps a small fortune from a bank robbery. As a matter of fact, the one who keeps the money is John, Willa’s son, and Powell, after coldly murdering Willa (in a scene with a photography that reminds us of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’s German expressionism) starts a pursuit of John and his sister which will end with the confrontation with Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish), the matriarchal figure who will face the perverted preacher.

In the simplistic regard of this film as a tale/religious allegory, one can see Harry Powell as the incarnation of evil in constant fight with good (this fight is attested in his sermons) and John Harper as the bearer of the heavy burden of sin – the money from the robbery – who walks his redeeming path towards the discharge of that load which, after all, prevents him from reuniting with his lost childhood.

Just like Laughton’s quotation above indicates, this film doesn’t mean to have a realistic quality, and one actually feels the dreamlike, or nightmare-like, ambience, through the 93 minutes of black and white photography. Mitchum perfectly incarnates – in one of the best performances in his career – the ambiguous, disturbing, threatening figure of the character, rehearsing in this controversial role what would be his famous trademark, the hard and stern (in)expression that so many times we’ve enjoyed in the westerns and films noir (and other genres) where he starred.

The film contains many theatrical elements and is covered with a vision of opposites that emphasize an underlying Manichaeism: strong contrasts of light and shadows, religious images that portray resistance and innocence but also the evil inherent to man and, finally, the words love and hate that Powell has tattooed on the fingers of his right and left hand, respectively. The reactions to Laughton’s unique (literally!) work, to this nightmare-tale that leaves no-one indifferent, are usually extreme, as well. I’m pleased with that, for that is a frequent quality in an exceptional work.

24 June 2006

Viagem ao Inferno via Whitechapel * A trip to Hell via Whitechapel

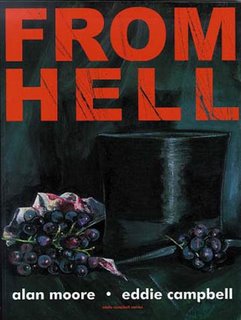

Alan Moore assumiu-se como um pioneiro do movimento iniciado nos anos 80 que facultou a elevação do estatuto da 9ª arte para lá das "histórias de quadradinhos" para crianças (e adultos pouco letrados). Depois de um esboço com V for Vendetta (recentemente adaptado para o cinema), conseguiu-o com Watchmen, uma graphic novel que tanto para leitores como para a crítica revolucionou o mundo dos super-heróis e transformou a experiência narrativa da banda desenhada em algo muito próximo da profundidade narrativa do romance, o que juntamente com a arte de Dave Gibbons, o artista que colocou a história de Moore em imagens, deu origem à única banda desenhada a receber um Hugo Award e a figurar entre os 100 melhores romances (de língua inglesa) da Time Magazine.

Alan Moore assumiu-se como um pioneiro do movimento iniciado nos anos 80 que facultou a elevação do estatuto da 9ª arte para lá das "histórias de quadradinhos" para crianças (e adultos pouco letrados). Depois de um esboço com V for Vendetta (recentemente adaptado para o cinema), conseguiu-o com Watchmen, uma graphic novel que tanto para leitores como para a crítica revolucionou o mundo dos super-heróis e transformou a experiência narrativa da banda desenhada em algo muito próximo da profundidade narrativa do romance, o que juntamente com a arte de Dave Gibbons, o artista que colocou a história de Moore em imagens, deu origem à única banda desenhada a receber um Hugo Award e a figurar entre os 100 melhores romances (de língua inglesa) da Time Magazine.Depois de Watchmen (e inúmeras outras obras), Alan Moore voltou a surpreender com From Hell. Quando se sugere que o tema central de From Hell é Jack o Estripador, Moore corrige dizendo que os crimes de Whitechapel são apenas um pretexto para um retrato profundo da época vitoriana e do advento do século XX. Tal como Watchmen, e indo até um pouco mais longe, From Hell é mais que uma simples graphic novel, entrando, nalguns aspectos, no campo do romance e inclusivamente do ensaio – especulativo mas fundamentado nas poucas fontes existentes, também elas carecendo de rigor histórico absoluto. É, acima de tudo, uma obra grandiosa, com as suas mais de 500 pranchas mais 66 páginas de anexos, 42 das quais com notas que, acima de tudo, fundamentam e explicam a teorização sobre o tema através de consulta bibliográfica e anotações de cariz histórico.

Trata-se, portanto, de ficção pontuada por fundamentos históricos que servem para dar coerência narrativa e verosimilhança (pergunto-me... será que Dan Brown já leu From Hell?...). Vemos, assim, os crimes hediondos de Jack o Estripador como uma trama real encabeçada pela própria Rainha Vitória que se vê forçada a tomar medidas desesperadas para salvar a honra da Coroa Britânica, chamando o cirurgião maçónico Sir William Gull para resolver o caso de uma situação de chantagem que tem por base o facto de o Príncipe Albert Victor ter engravidado e casado com Annie Crook, uma lojista da classe trabalhadora. Por muito apetecível e sedutora que esta versão dos acontecimentos nos pareça, sabemos que, e apesar do confronto com fontes documentais – por vezes escassas e contraditórias – estamos no terreno pantanoso da suposição, o que no entanto não torna a obra menos excitante.

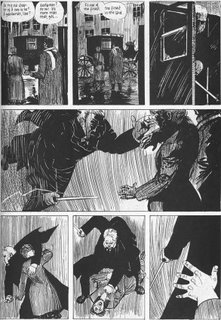

Eddie Campbell acompanha de forma competente o argumento de Moore com um desenho de traço fino com silhuetas e sombras extraídas de abundantes traços paralelos ou cruzados, ou mesmo muitas vezes com um fundo totalmente negro – obrigatoriamente com arte-final a preto e branco para mais facilmente criar o ambiente nocturno e sombrio das ruas londrinas do século XIX.

From Hell são 16 capítulos (mais anotações e anexos) que facilmente prendem o leitor, quer nos momentos mais gráficos, com várias páginas seguidas de pranchas silenciosas, muitas vezes com imagens fortes cujo impacto nem o preto e branco consegue atenuar, quer nos muitos momentos com características mais de romance que de banda desenhada, em que, apesar de nada de novo surgir nas imagens, o texto é crucial para o desenvolvimento da profundidade das personagens. Numa história em que nada são certezas ao longo do desenrolar da acção, a única certeza que fica é a de que Alan Moore continuará certamente a surpreender-nos com obras-primas que fazem jus à sua crescente aceitação - no meio dos comic books e fora dele.

After Watchmen (and a myriad of other works), Alan Moore surprised once more with From Hell. When it is suggested that From Hell’s main subject is Jack the Ripper, Moore corrects this assumption by saying that the Whitechapel crimes are only a pretext for an insightful portrait of the Victorian Age and the advent of the 20th century. Just like Watchmen, and going even a bit further, From Hell is more than a mere graphic novel, exploring, in some aspects, the field of the novel and inclusively the essay – speculative but grounded in the few existing sources, these latter also lacking absolute historical accuracy. It is, most of all, an immense work, with its more than 500 boards plus 66 pages of annexes including 42 with annotations that, above all, ground and explain the theorisation on the subject through bibliographical research and historical annotations.

It is, therefore, fiction punctuated with historical groundings that are used to provide narrative coherence and likelihood (I wonder… has Dan Brown already read From Hell?...). Thus we see Jack the Ripper’s heinous crimes as a royal plot headed by Queen Vic herself who is forced to take desperate measures to safeguard the honour of the British Crown, calling the mason surgeon Sir William Gull to solve the case of a blackmail situation based on the fact that Prince Albert Victor had knocked up and married Annie Crook, a working-class shop attendant. Though this version of events sounds amusing and appealing, we know that (and despite the confrontation with documental sources – sometimes scarce and contradictory) we are in the muddy lands of supposition, which nevertheless doesn’t make it less exciting.

Eddie Campbell proficiently follows Moore’s script with an artwork made up of thin outlines with silhouettes and shadows obtained from copious parallel or crossed lines, or even, quite often, with a totally black background – forcibly with a black and white final art to recreate more easily the nocturnal and gloomy ambience of the 19th century London streets.

From Hell is a set of 16 chapters (plus annotations and annexes) that easily takes hold of the reader, both in the more graphic moments, with several pages in a row with silent boards, often with strong images with an impact that can’t be lightened by the black and white, and in the numerous moments which resemble more the novel than the comic book, in which, although nothing new shows up in the images, the text is critical for the development of the characters’ depth. In a story where nothing is certain throughout the action, the only certainty that remains is that Alan Moore will surely keep surprising us with master works that confirm his increasing acceptance – both in the comics medium and outside it.

22 June 2006

Alice vezes dois * Alice times two

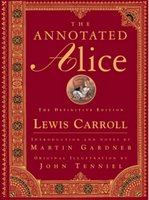

O Rev. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), professor de Matemática em Oxford, ficou para a história não como o eminente matemático que publicou diversos e relevantes tratados (Euclid and his Modern Rivals, de 1879 é o mais conhecido), mas como Lewis Carroll, o autor de Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) e Through the Looking-Glass (1872), obras declaradamente infantis mas com uma série de características que as tornam apelativas e bastante interessantes para leitores mais amadurecidos. As aventuras de Alice foram originalmente contadas por Carroll à pequena Alice Liddell e às suas duas irmãs num dia de Verão de 1862, durante um passeio de barco, e no Natal desse ano Carroll ofereceu o livro a Alice com a dedicatória A Christmas Gift to a Dear Child in Memory of a Summer Day. Só 3 anos mais tarde seria publicado como Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, com as sobejamente conhecidas ilustrações de John Tenniel (a primeira versão tinha sido ilustrada pelo próprio Carroll).

O Rev. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), professor de Matemática em Oxford, ficou para a história não como o eminente matemático que publicou diversos e relevantes tratados (Euclid and his Modern Rivals, de 1879 é o mais conhecido), mas como Lewis Carroll, o autor de Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) e Through the Looking-Glass (1872), obras declaradamente infantis mas com uma série de características que as tornam apelativas e bastante interessantes para leitores mais amadurecidos. As aventuras de Alice foram originalmente contadas por Carroll à pequena Alice Liddell e às suas duas irmãs num dia de Verão de 1862, durante um passeio de barco, e no Natal desse ano Carroll ofereceu o livro a Alice com a dedicatória A Christmas Gift to a Dear Child in Memory of a Summer Day. Só 3 anos mais tarde seria publicado como Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, com as sobejamente conhecidas ilustrações de John Tenniel (a primeira versão tinha sido ilustrada pelo próprio Carroll).A segunda, numa perspectiva mais lúdica, é a edição de Alice's Adventures in Wonderland ilustrada por Anthony Browne. Trata-se de uma interessante alternativa às ilustrações de Tenniel, cujo pendor surrealista se encaixa perfeitamente no ambiente onírico da obra. Esta edição ganhou o Emil/Kurt Maschler Award e garantidamente encantará as crianças com as suas cores fortes e o seu humor, mas também adultos que apreciem ilustração de inegável criatividade artística. A obra vive numa comunicação constante com as imagens e, aliás, citando a protagonista, "para que serve um livro," pensou Alice, "sem imagens ou conversas?"