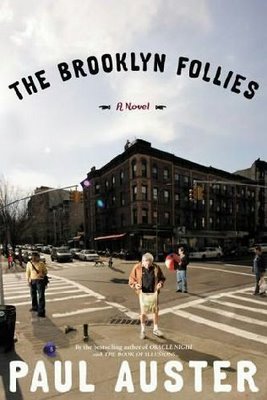

Não se deixem enganar. Por detrás de uma narrativa com um estilo literário - o do narrador - aparentemente intuitivo e carregado, ao mesmo tempo, de uma simplicidade linear e de ornamentos que parecem evocar uma escrita do século XIX (there is no escape from the wretchedness that stalks the earth), esconde-se um mundo de alusões e referências que tornam The Brooklyn Follies uma das mais inspiradas obras de Paul Auster.

Quem narra a história é Nathan Glass, um angariador de seguros reformado que resolve tornar-se um autodidacta das letras, e é preciso ser-se um grande autor como Auster para assumir este risco de deixar um fraco escritor como Nathan controlar a narrativa e ainda assim deslumbrar o leitor. Talvez porque há coisas que só conseguem assumir uma grande expressividade através das palavras simples de uma pessoa simples – a honesta e até ingénua capacidade de encantamento e de ilusão torna-se mais credível na voz do ignorante que do homem sábio. Ou num outro ângulo, e usando uma analogia shakespeariana, Iago não profere plenamente as palavras de acusação, ele sabe que o efeito será mais devastador se for o próprio Othello a verbalizar o corolário da suspeita que o irá destruir.

Apesar de tudo, o Auster de sempre está lá: mais uma vez um começo abrupto – I was loking for a quiet place to die; outra vez uma personagem-escritor; outra vez um livro-dentro-do-livro; outra vez Brooklyn; outra vez uma vontade incomensurável mas insatisfeita de que certos pormenores, que nos são acenados en passant, tivessem sido mais desenvolvidos porque temos a certeza que neles se escondem outros filões – não seria a primeira vez que Auster transportava um detalhe, uma personagem ou uma situação de um romance para o desenvolver noutro; outra vez tantos traços que constituem, com propriedade, o que já se pode intitular de estilo austeriano - mas não austero... Repetitivo? Nem pensar. Apesar de tantos referenciais e traços comuns, The Brooklyn Follies é uma obra completamente nova, e não o é apenas pelo estilo imposto pela voz do narrador que, aos olhos do leitor de Auster é como a Coca-Cola do slogan pessoano, primeiro estranha-se, depois entranha-se.

The Book of Human Folly, o livro dentro de The Brooklyn Follies, o aglomerado de pequenas histórias, episódios, frases soltas e descrições que Nathan Glass vai escrevendo e revelando ao longo do romance é uma verdadeira caixa de surpresas e mostra bem o talento de Auster para compor anedotas da vida humana com uma grande dose de verosimilhança (já comprovado também no seu National Story Project que resultou na colectânea True Tales of American Life). São elas as anedotas que compõem os traços da anedota maior, pois anedótica é também a vida de Nathan, que, como bom comediante da vida, encontra um parceiro à altura da comédia, o volumoso sobrinho Tom Wood, desaparecido da sua vida há anos e reencontrado em Brooklyn nesta nova fase da(s) sua(s) vida(s). As associações podem ser inúmeras, desde a parelha cómica de Laurel e Hardy à estática união tragicómica de Vladimir e Estragon, mas certo é que a relação das duas personagens acaba por converter-se, em grande medida, no motor que impulsiona a acção.

Poderia ainda, em conclusão, referir as temáticas abordadas ao longo das “follies”, elas próprias as “follies” da vida – a paixão, a amizade, a velhice, o sonho, a homossexualidade, a ambição, o desencantamento… – mas todos esses aspectos, e muitos outros, significam apenas uma nova roupagem para o grande fio condutor, a intemporalidade que começamos a encontrar padronizada na obra de Auster: o caminho percorrido pela vida humana, repleto de acasos, coincidências, desvios, regressos, surpresas, encontros e desencontros e, acima de tudo, muitas loucuras.

Quem narra a história é Nathan Glass, um angariador de seguros reformado que resolve tornar-se um autodidacta das letras, e é preciso ser-se um grande autor como Auster para assumir este risco de deixar um fraco escritor como Nathan controlar a narrativa e ainda assim deslumbrar o leitor. Talvez porque há coisas que só conseguem assumir uma grande expressividade através das palavras simples de uma pessoa simples – a honesta e até ingénua capacidade de encantamento e de ilusão torna-se mais credível na voz do ignorante que do homem sábio. Ou num outro ângulo, e usando uma analogia shakespeariana, Iago não profere plenamente as palavras de acusação, ele sabe que o efeito será mais devastador se for o próprio Othello a verbalizar o corolário da suspeita que o irá destruir.

Apesar de tudo, o Auster de sempre está lá: mais uma vez um começo abrupto – I was loking for a quiet place to die; outra vez uma personagem-escritor; outra vez um livro-dentro-do-livro; outra vez Brooklyn; outra vez uma vontade incomensurável mas insatisfeita de que certos pormenores, que nos são acenados en passant, tivessem sido mais desenvolvidos porque temos a certeza que neles se escondem outros filões – não seria a primeira vez que Auster transportava um detalhe, uma personagem ou uma situação de um romance para o desenvolver noutro; outra vez tantos traços que constituem, com propriedade, o que já se pode intitular de estilo austeriano - mas não austero... Repetitivo? Nem pensar. Apesar de tantos referenciais e traços comuns, The Brooklyn Follies é uma obra completamente nova, e não o é apenas pelo estilo imposto pela voz do narrador que, aos olhos do leitor de Auster é como a Coca-Cola do slogan pessoano, primeiro estranha-se, depois entranha-se.

The Book of Human Folly, o livro dentro de The Brooklyn Follies, o aglomerado de pequenas histórias, episódios, frases soltas e descrições que Nathan Glass vai escrevendo e revelando ao longo do romance é uma verdadeira caixa de surpresas e mostra bem o talento de Auster para compor anedotas da vida humana com uma grande dose de verosimilhança (já comprovado também no seu National Story Project que resultou na colectânea True Tales of American Life). São elas as anedotas que compõem os traços da anedota maior, pois anedótica é também a vida de Nathan, que, como bom comediante da vida, encontra um parceiro à altura da comédia, o volumoso sobrinho Tom Wood, desaparecido da sua vida há anos e reencontrado em Brooklyn nesta nova fase da(s) sua(s) vida(s). As associações podem ser inúmeras, desde a parelha cómica de Laurel e Hardy à estática união tragicómica de Vladimir e Estragon, mas certo é que a relação das duas personagens acaba por converter-se, em grande medida, no motor que impulsiona a acção.

Poderia ainda, em conclusão, referir as temáticas abordadas ao longo das “follies”, elas próprias as “follies” da vida – a paixão, a amizade, a velhice, o sonho, a homossexualidade, a ambição, o desencantamento… – mas todos esses aspectos, e muitos outros, significam apenas uma nova roupagem para o grande fio condutor, a intemporalidade que começamos a encontrar padronizada na obra de Auster: o caminho percorrido pela vida humana, repleto de acasos, coincidências, desvios, regressos, surpresas, encontros e desencontros e, acima de tudo, muitas loucuras.

Paul Auster caricature © Anthony Hare 2005

Do not fool yourselves. Behind a narrative with a literary style – the narrator’s – apparently intuitive and simultaneously filled with a straight simplicity and ornaments that seem to evoke a 19th century writing (there is no escape from the wretchedness that stalks the earth), a world of allusions and references are hiding, and these make The Brooklyn Follies one of the most inspired works of Paul Auster.

The narrator of the story is Nathan Glass, a retired insurance clerk who decides to become a self-taught writer, and you need to be a great author like Auster to take the risk of letting a feeble writer like Nathan control the narrative and still fascinate the reader. Maybe that’s because there are things that can only assume a great expressiveness through the simple words of a simple person – the honest and yet naïve talent of enchantment and illusion becomes more plausible through the voice of the ignorant than through that of the wise man. Or, in a different perspective, and using a Shakespearean analogy, Iago does not fully pronounce the words of accusation, he knows the effect will be far more devastating if Othello himself verbalises the corollary of suspicion that will destroy him.

In spite of all, the usual Auster is there: once more an abrupt beginning – I was looking for a quiet place to die; once more a character-writer; once more a book-within-the-book; once more Brooklyn; once more an immeasurable yet unfulfilled will that some details, waved at us en passant, had been more deeply developed because we are sure that other springs are hidden there – it wouldn’t be the first time that Auster carries a detail, a character or a situation from a novel to develop it in another one; once more so many traces that make up, on their own right, what can already be entitled an Austerian – but not austere – style… Repetitive? No way. Despite so many references and common traces, The Brooklyn Follies is a completely new work, and not just because of the style imposed by the narrator’s voice which, to the eyes of the Auster reader is like Coca-Cola in the advertising catch-phrase devised by the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, first you drive it out, then it drives into you.

The Book of Human Folly, the book within The Brooklyn Follies, the agglomerate of short stories, episodes, loose sentences and descriptions that Nathan Glass writes and reveals throughout the novel is a real prestidigitator’s hat and shows well Auster’ talent to compose anecdotes of human life with a large amount of likelihood (already proven in his National Story Project, which led to the collection True Tales of American Life). These are the anecdotes that make up the traces of the bigger anecdote, for Nathan’s life is also anecdotic – and like any good comedian of life, he finds himself a suitable sidekick for the comedy, his huge nephew Tom Wood, who had vanished from his life years ago and was reencountered in Brooklyn during the new stage of his (their) life (lives). The associations may be countless, from the comedy partnership of Laurel and Hardy to the static tragicomedy union of Vladimir and Estragon, but what is certain is that the relationship between the two characters ends up becoming, to a great extent, the fuel that propels the action.I could still mention, to conclude, the themes focused throughout the “follies”, the “follies” of life by themselves – passion, friendship, ageing, dream, homosexuality, ambition, disillusion… – but all those aspects, and many others, only mean a new wrapping for the big streamline, the timelessness that we start to find as a pattern in Auster’s work: the path taken by human life, filled with chance, coincidence, detours, returns, surprises, encounters and evasions and, above all, a lot of folly.

No comments:

Post a Comment