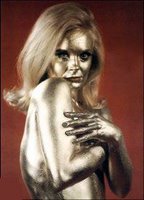

A actriz britânica Shirley Eaton (1937-...) ficou imortalizada na

história do cinema pela sua participação em Goldfinger (1964) de Guy Hamilton, o terceiro da série James Bond protagonizado por Sean Connery: apesar de relegada para segundo plano pela ‘bondgirl’ Honor Pussy Galore Blackman, ninguém esquecerá o corpo de Eaton completamente coberto de tinta dourada. Alguns anos antes desse banho de spray dourado, Shirley Eaton protagonizou What a Carve Up! (1961), uma comédia negra de Pat Jackson (baseda livremente em The Ghoul (1933) de T. Hayes Hunter), que, se bem que a comparação seja, a meu ver, um pouco depreciativa e até injusta, se aproximava um pouco do estilo da fastidiosa série de filmes de comédia Carry On.../Com jeito vai... (30 filmes entre 1958 e 1978, mais uma tentativa de 'reanimação' em 1992 - é obra!).

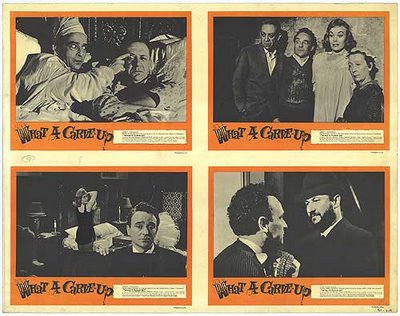

história do cinema pela sua participação em Goldfinger (1964) de Guy Hamilton, o terceiro da série James Bond protagonizado por Sean Connery: apesar de relegada para segundo plano pela ‘bondgirl’ Honor Pussy Galore Blackman, ninguém esquecerá o corpo de Eaton completamente coberto de tinta dourada. Alguns anos antes desse banho de spray dourado, Shirley Eaton protagonizou What a Carve Up! (1961), uma comédia negra de Pat Jackson (baseda livremente em The Ghoul (1933) de T. Hayes Hunter), que, se bem que a comparação seja, a meu ver, um pouco depreciativa e até injusta, se aproximava um pouco do estilo da fastidiosa série de filmes de comédia Carry On.../Com jeito vai... (30 filmes entre 1958 e 1978, mais uma tentativa de 'reanimação' em 1992 - é obra!).Este filme, e especialmente a cena em que Linda, a personagem representada por Eaton, é surpreendida a despir-se no quarto por um embaraçado Ernie (Kenneth Connor), constitui - juntamente com Yuri Gagarin, Orfeu (o de Jean Cocteau), tabletes de chocolate e cassetes de vídeo - uma das obsessões recorrentes de Michael Owen, o protagonista do romance de 1994

de Jonathan Coe que pediu emprestado o título ao filme de Jackson.

de Jonathan Coe que pediu emprestado o título ao filme de Jackson.A narrativa segue duas linhas paralelas, estabelecidas logo no prólogo e apresentadas ao longo da primeira parte sempre em capítulos alternados. Por um lado, o desvendar da vida do obscuro e angustiado escritor Michael Owen, que tem como fio condutor a misteriosa comissão da biografia de uma das mais ricas e influentes famílias britânicas - a família Winshaw. Por outro, a revelação dos membros da terceira geração dessa família - a narrativa enquadra precisamente três gerações de Winshaws (17 ao todo), o que tornaria as primeiras páginas do livro algo confusas, não fora o recurso a uma árvore genealógica logo no início do prólogo, cuja consulta ajuda o leitor a localizar as personagens na estrutura familiar. A informação narrada nestes capítulos é obtida a partir das pesquisas de Michael para a composição da biografia, incluindo fragmentos de programas de televisão, artigos de revistas, etc., o que nos faz seguir durante toda esta primeira parte a perspectiva de Michael, que por sua vez assume a dificuldade em manter a realidade separada da ficção à medida que se vai envolvendo cada vez mais com os Winshaws.

A segunda parte decorre na lúgubre mansão da família, onde é lido o testamento de Mortimer Winshaw. Nesta momento em que todas as peças do puzzle se encaixam através das esperadas revelações (como num jogo de Cluedo), num misto de romance de Agatha Christie e filme de Terence Fischer, vemos a oportunidade de Michael finalmente se encontrar cara a cara com os Winshaws que ainda estão vivos, apenas para confirmar através dos acontecimentos que a sua relação com a família ultrapassa o carácter profissional da escrita biográfica. Mais ainda, essa é a noite em que o escritor que desde criança vive obcecado com What a Carve Up! (o filme) confirma finalmente a sensação - que sente desde que o vira com nove anos - de que não é um mero espectador mas uma personagem que o vive por dentro sem qualquer controlo dos acontecimentos – facto corroborado pelo facto de Michael deixar de ser narrador na primeira pessoa e com o clímax no momento em que encarna Kenneth Connor e surpreende a sua própria Shirley Eaton no quarto da mansão, culminando assim o processo que se adivinha com o constante dejà vu da cena ao longo da narrativa.

A família Winshaw é um retrato cru e mordaz, centrado entre os mandatos conservadores de Margaret Thatcher e John Major, de uma Inglaterra literalmente despedaçada (carved up) por um pequeno grupo dominante que sistematicamente mina as reformas do Seviço Nacional de Saúde, arrasa sem escrúpulos o mercado bolsista, favorece artistas em troca de favores sexuais, inunda o mercado alimentar com carnes provenientes de criações com duvidosos métodos de rentabilização e vende armas a Saddam Hussein enquanto se espera que este invada o Kuwait (o livro foca com alguma persistência a ansiedade da expectativa de uma guerra do golfo que está iminente). Muito mais que uma simples sátira socio-política, esta narrativa é uma experiência de leitura extremamente completa e grandemente enriquecida através da mistura de géneros, e influências, especialmente as de origem cinematográfica: o cinema contamina claramente este livro, o que apesar de tudo não é surpreendente - não esqueçamos que Coe também se move nos meios cinematográficos tendo escrito biografias de Humphrey Bogart e de James Stewart.

The British actress Shirley Eaton (1937-...) was immortalised in the history of cinema by her appearance in Guy Hamilton’s Goldfinger (1964), the third in the James Bond series starring Sean Connery: although hidden under the shadow of the ‘bondgirl’ Honor Pussy Galore Blackman, no-one will forget Eaton’s body completely covered in golden paint. A few years before that golden spray bath, Shirley Eaton had starred in What a Carve Up! (1961), Pat Jackson’s black comedy (freely inspired in T. Hayes Hunter’s The Ghoul (1933)), which, even if the comparison seems, to me, a bit derogative and even unfair, came a bit close to the style of the tedious comedy film series Carry On... (30 films from 1958 and 1978, plus one revival attempt in 1992 – that’s something!).

This film, and especially the scene where Linda, the character played by Eaton, is surprised undressing in her room by an embarrassed Ernie (Kenneth Connor), is one of Michael Owen’s recurring obsessions – together with Yuri Gagarin, Orpheus (Jean Cocteau’s), chocolate bars and videotapes. Owen is the main character of the 1994 Jonathan Coe’s novel which borrowed the title from Jackson’s film.

The narrative follows two parallel lines, established right away in the prologue and presented throughout part one, always in alternate chapters. On the one hand, the disclosure of the live of obscure and anguished writer Michael Owen, which gravitates around the mysterious commission for the biography of one of the richest and most influent (and vilest) British families – the Winshaw family. On the other, the revelation of the members of the family’s third generation – the narrative encloses precisely three generations of Winshaws (17 of them), which would make the first pages of the book somehow confusing without the help of the family tree printed at the beginning of the prologue. It does help the reader locate the characters within the family structure. The information narrated in these chapters is obtained from Michael’s researches for the composition of the biography, including fragments of television programmes, magazine articles, etc., which makes us follow Michael’s perspective for the whole part one. He actually assumes how difficult it is to keep reality and fiction apart as he gets more and more involved with the Winshaws.

Part two takes place in the lugubrious family mansion, where Mortimer Winshaw’s will is read. At this moment in which every piece of the puzzle fits via the expected revelations (as in a Cluedo game), in a mixture of Agatha Christie’s novel and Terence Fischer’s film, we see Michael’s opportunity, at last, to meet the remaining Winshaws face to face, only to confirm through the events that his relation with the family goes far beyond the professional status of biographical writing. Moreover, that is the night where the writer, who had been obsessed with What a Carve Up! (the film) since his childhood, finally confirms the feeling – which he’d had since he first saw it at the age of nine – that he is not a mere spectator, but a character living it from the inside without any control of the events – fact confirmed by the fact that Michael stops being the first person narrator, and by the climactic moment where he embodies Kenneth Connor and surprises his very own Shirley Eaton in the mansion room, concluding thus the process one could guess with the constant dejà vu of this scene throughout the narrative.

The Winshaw family is a raw and poignant portrait, centred between the conservative administrations of Margaret Thatcher and John Major, of an England literally carved up by a small dominant group that systematically undermines the National Health Service reforms, ruthlessly knocks down the stock market, favours artists in return for sexual favours, fills up the food market with meat that comes from farms with dubious methods of cost-effectiveness and sells guns to Saddam Hussein while waiting for him to invade Kuwait (the book focuses persistently on the anticipating anxiety of an imminent gulf war). Much more than a simple socio-political satire, this narrative is an extremely comprehensive reading experience and one greatly enriched by the mixture of genres and influences, especially those of cinematic origin: cinema clearly crawls into the book, which, after all, is not surprising at all if we bear in mind that Coe also moves in the cinematographic media, since he wrote Humphrey Bogart and James Stewart’s biographies.

This film, and especially the scene where Linda, the character played by Eaton, is surprised undressing in her room by an embarrassed Ernie (Kenneth Connor), is one of Michael Owen’s recurring obsessions – together with Yuri Gagarin, Orpheus (Jean Cocteau’s), chocolate bars and videotapes. Owen is the main character of the 1994 Jonathan Coe’s novel which borrowed the title from Jackson’s film.

The narrative follows two parallel lines, established right away in the prologue and presented throughout part one, always in alternate chapters. On the one hand, the disclosure of the live of obscure and anguished writer Michael Owen, which gravitates around the mysterious commission for the biography of one of the richest and most influent (and vilest) British families – the Winshaw family. On the other, the revelation of the members of the family’s third generation – the narrative encloses precisely three generations of Winshaws (17 of them), which would make the first pages of the book somehow confusing without the help of the family tree printed at the beginning of the prologue. It does help the reader locate the characters within the family structure. The information narrated in these chapters is obtained from Michael’s researches for the composition of the biography, including fragments of television programmes, magazine articles, etc., which makes us follow Michael’s perspective for the whole part one. He actually assumes how difficult it is to keep reality and fiction apart as he gets more and more involved with the Winshaws.

Part two takes place in the lugubrious family mansion, where Mortimer Winshaw’s will is read. At this moment in which every piece of the puzzle fits via the expected revelations (as in a Cluedo game), in a mixture of Agatha Christie’s novel and Terence Fischer’s film, we see Michael’s opportunity, at last, to meet the remaining Winshaws face to face, only to confirm through the events that his relation with the family goes far beyond the professional status of biographical writing. Moreover, that is the night where the writer, who had been obsessed with What a Carve Up! (the film) since his childhood, finally confirms the feeling – which he’d had since he first saw it at the age of nine – that he is not a mere spectator, but a character living it from the inside without any control of the events – fact confirmed by the fact that Michael stops being the first person narrator, and by the climactic moment where he embodies Kenneth Connor and surprises his very own Shirley Eaton in the mansion room, concluding thus the process one could guess with the constant dejà vu of this scene throughout the narrative.

The Winshaw family is a raw and poignant portrait, centred between the conservative administrations of Margaret Thatcher and John Major, of an England literally carved up by a small dominant group that systematically undermines the National Health Service reforms, ruthlessly knocks down the stock market, favours artists in return for sexual favours, fills up the food market with meat that comes from farms with dubious methods of cost-effectiveness and sells guns to Saddam Hussein while waiting for him to invade Kuwait (the book focuses persistently on the anticipating anxiety of an imminent gulf war). Much more than a simple socio-political satire, this narrative is an extremely comprehensive reading experience and one greatly enriched by the mixture of genres and influences, especially those of cinematic origin: cinema clearly crawls into the book, which, after all, is not surprising at all if we bear in mind that Coe also moves in the cinematographic media, since he wrote Humphrey Bogart and James Stewart’s biographies.

Jonathan Coe's bibliography:

The Accidental Woman Duckworth, 1987

A Touch of Love Duckworth, 1989

The Dwarves of Death Fourth Estate, 1990

Humphrey Bogart: Take It and Like It Bloomsbury, 1991

James Stewart: Leading Man Bloomsbury, 1994

What a Carve Up! Viking, 1994

The House of Sleep Viking, 1997

The Rotters' Club Viking, 2001

Like a Fiery Elephant: The Story of B. S. Johnson Picador, 2004

The Closed Circle Viking, 2004

Prizes and awards:

1995 Mail on Sunday/John Llewellyn Rhys Prize What a Carve Up!

1995 Prix du Meilleur Livre Etranger (France) What a Carve Up!

1997 Writers' Guild Award (Best Fiction) The House of Sleep

1998 Prix Médicis Etranger (France) The House of Sleep

2001 Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize The Rotters' Club

2005 Samuel Johnson Prize Like a Fiery Elephant: The Story of B. S. Johnson

2006 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award The Closed Circle